Celebrating 30 years worth of fanaticism and community in the cult of Ashley ‘Ash’ Williams.

Thanks to our Star Trekian utopia of VOD insta-satisfaction (“Number One, slap The Greasy Strangler on the view screen!”), it’s becoming difficult to remember the ruthless savagery of that bygone VHS hunt. I spent far too many days roaming my hometown and neighboring cities chasing down lesser-known Kurosawas, the Critters sequels, and the seemingly always elusive pre-Mad Max apocalyptic mindfuck, A Boy and His Dog. Too often I had to settle for less, and rewatch Police Academy 4 instead of the highbrow hilarity of Zapped! cuz some other Scott Baio devotee had the local Power Video on stakeout. If your tastes in cinema aligned with the Blockbuster new release guarantee then you were golden, but us degenerates with a predilection for Roger Corman, and movies made before our births were doomed to the endless quest. Which, of course, doomed our family and friends to our equally infinite rants for VHS nostalgia. After all, having dedicated entire days of our lives chasing down Cannibal Holocaust, we have to justify our obsession. It was worth it.

As I got older, the anger and frustration of the hunt gave way to pride and community. I was not alone in my fanaticism. That Scott Baio devotee hidden in the bushes was not my enemy, he was my lifelong compatriot. Two hands reaching for the same Evil Dead II tape on the shelf would not result in gladiatorial combat, but a black hole debate of KNB EFX vs. Tom Savini. The Evil Dead trilogy was (and still is) a binding agent for my friendship. I can talk all day long on all manner of film, but a tangential reference to Ashley Williams or Ram-O-Cam ingenuity will gain you immediate entrance into my inner circle of dork.

Very few had the privilege of witnessing The Evil Dead or Evil Dead II on the big screen. Sam Raimi’s original film is the very definition of a cult classic (crack open your Merriam Websters, it’s true), and while the sequel was a modest success for its budget, the groovy sect of Bruce Campbell was eventually built on the backs of rental sales. Fandom is a finicky creature; for it to grow, the individual in the community needs to feel like they belong to a limited group. The cult must appear small enough to feel special, but large enough to fend off isolation. It’s a sweet spot cocktail impossible to replicate no matter how many Machetes or Wolf Cops that drown the market. Basically, you need a film that’s successful enough to spawn a line of Rotten Cotton tee shirts to lure in fresh fish, and no more.

20 years ago, let alone 30 years ago, a VHS copy of The Evil Dead was as nearly impossible to acquire as Zapped! I didn’t have a chance to see that incredibly earnest first film until years after my obsession with Evil Dead II’s splatstick had developed into a full-blown mania. In light of the sequel, The Evil Dead is a challenging, possibly confusing watch. The micro budgeted spook story of Ashley “Ash” Williams’ encounter with an ancient demonic possession is an inventive monster mash that will forever continue to inspire filmmakers from around the world. If Sam Raimi and his friends could venture into the woods of Tennessee and pull off a terror tale like The Evil Dead than you can too.

Having suffered through the studio system for his sophomore slump Crimewave, Raimi returned to the horror genre in an effort to maintain his precarious career. Thanks to Stephen King’s glowing review of The Evil Dead (“…The most ferociously original horror film of the year…”), the director of Maximum Overdrive was able to convince his producer, Dino De Laurentis to back a second dip into the Necronomicon Ex-Mortis. The original film had decent returns in Italy, and the infamous producer broke off 3.6 million dollars for Raimi and crew to resurrect the cabin set inside the gymnasium of a junior high school in North Carolina. Still working on scraps, original plans for a time traveling adventure to the Middle Ages would have to wait for the follow-up flick, Army of Darkness.

Failing to acquire the rights to the original film, Raimi and co-writer Scott Spiegel tossed continuity to the wind, and elected to recap/rework The Evil Dead into the first fifteen minutes of Evil Dead II. Ditching the college friends, the sequel kept Bruce Campbell’s Ash and his girlfriend Linda (now played by actress Denise Bixler), but rushed the deadite takeover of the ill-fated cabin in the woods so that they could speed their way into the Three Stooges hysterics that obviously drove their passion. Appearing less interested in plunging pencils into ankles or branches into vaginas, the entertainment of Evil Dead II is found in visual puns, pratfalls, and Bruce Campbell’s vaudevillian theatrics. It took the sequel for Sam Raimi to reveal himself as an auteur, and as such, Evil Dead II marks itself as a momentous coming out party for one of genre cinema’s most playful maestros.

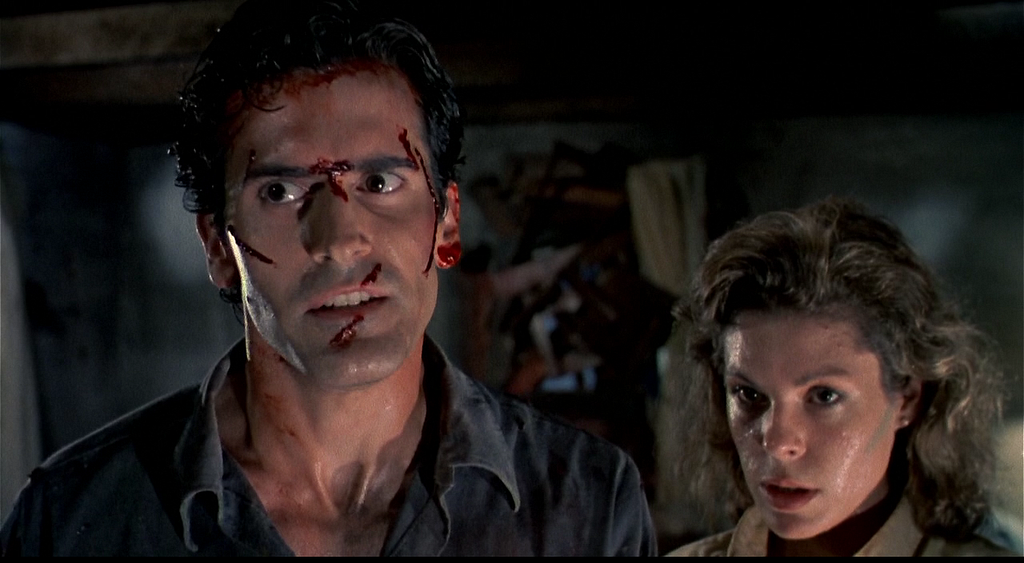

Keeping that in mind, for Sam Raimi’s cartoonish vision to succeed, he needed his own Wile E. Coyote to torment. Bruce Campbell is the man with the cheezeball charm, and the elastic face. As perfectly acceptable as he is to terrorize in The Evil Dead, in Part II, Campbell explodes with hilarious yet often unsettling energy. One of the few humans on this planet who can actually sell comic booky, expository conversations with himself, Campbell’s Ash has no difficulty connecting with his audience through sheer persuasion. Certainly taking more glee than the deadites, Raimi delights in torturing Campbell through a series of rag doll stunts, and the man who would be king commits with sadomasochistic abandon.

Ash is a lovable dolt of a hero that we gladly cheer on, but through the process of rabid rewatches, we likewise appreciate the amount of bodily harm that has cursed his very existence. After decapitating Linda, fleeing the dark bowers of the forest, and experiencing a supernatural eradication of the daylight, Campbell grumbles a command inward, “I gotta get a grip on myself here.” But that’s the last thing we want. The true pleasures of the Evil Dead series come from Ash’s Energizer Bunny spirit. Kandarian demons joyously tear into his flesh and mind, but the S-Mart slacker keeps going and going and going.

These tortures ripped from the pages of The Book of the Dead do take their toll on our hero, and Evil Dead II does have room in its runtime for horror and sorrow even if it’s preoccupied with physical comedy. Ash does not shake off this punishment in the same way that other 80s icons may have; despite his best efforts, he is no John Rambo. Chainsawing off your hand after it goes bad, and bobbing with your animated furniture will put more than a slight crack in your sanity. The resulting howls that burst forth from Ash’s resulting mental collapse are riotous, but also deeply upsetting.

Who’s laughing now? Really, none of us should be. Linda’s beef jerky, stop-motion pirouetting results in a severed head locked in the vise of ye old workshed. Ash gives his lady’s dome a pointed index, “You’re going down!” but for all his gesticulating, he is destroyed by a psychological assault of romantic pleading. The manner in which Linda’s latexed fiend reverts to her old self is utterly heartbreaking. If not surrounded by guffawing deer trophies and snickering desk lamps you’d probably drown in sympathy. It’s an ugly scene.

Evil Dead II is a go-for-broke declaration of talent. Sam Raimi and Scott Spiegel refuse to settle for a simple zombies in the woods story which could have easily placated its audience. Their kitchen sink is piled with undead girlfriends, psychotic appendages, wisecracking doppelgangers, well-meaning archeologists, revenge-fueled hillbillies, a gigantic rotten applehead demon, and buckets of red, green, yellow, and black blood (gotta keep that rating R with all the colors of the rainbow). If Raimi was going down he was not going away without unleashing a beastly bonkers mixture of genre upon the cinematic landscape.

Thankfully, fandom responded with a new religious order: The Cult of The Evil Dead. We’ve got tee shirts, action figures, video games, companion books, and a television spin-off looking to lure in newbies. You cannot drop a hilarious, gory cocktail like Evil Dead II on an unsuspecting market and fade away into obscurity. Sam Raimi is that rare breed; he’s a creator who was able to return to the property that made his name, absolutely reimagine it, and found encouragement to take his supposedly outdated Three Stooges heart into whatever tale sparked his fancy. Whether you wanted it or not, that heart beats forcefully in the bodies of his pulp hero Darkman, his western The Quick and the Dead, his spectacular Spider-Man, and Oz The Great and Powerful. And! You can find all of those singular exploits with the click of a button, as there is no need to declare war with your neighbors over a VHS tape.

Getting a Grip on ‘Evil Dead II’ was originally published in Film School Rejects on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.